Part Two of "A Wake Island Helmet." See part one at:

http://erasgone.blogspot.com/2012/08/a-wake-island-helmet-part-one-dodging.html

With the exception of a handful of

senior military officers and contractors held indoors, the captives remained

three days and two nights on the rocky runway after the surrender.

Leal Henderson Russell of La Grande, Oregon,

wrote in his otherwise optimistic diary: 23 December—". . . Rocks hard,

rain, wind, no cover and few clothes.

Bread and water. Very uncomfortable night." 24 December—"Still

on the rock-pile.

Very hard on the

unclothed men and those who are ill.

Many have dysentery. . . Men hard to control while food and water being

passed out.

Act like wolves. . .

."

|

| Leal Russell's signature on the sun helmet. Courtesy Glen Binge Family. |

Tensions of the previous days

relaxed a bit on Christmas morning.

One

contractor remembered that they were allowed to retrieve clothing, food, and

tobacco from their dugouts.

Russell recalled that the POWs were allowed

to bury their dead and were fed well for the first time.

They were marched to the north end of Wake

Island and put into the barracks they

had used before the beginning of hostilities.

Several 40-man barracks were packed with 150 men each, but the men had

shelter at last.

He recorded on 27

December: "Japanese treating us with reasonable consideration."

Rodney Kephart, the young carpenter from

Boise remembered: "We slept so well even the screaming of the Japs didn't

disturb us - that was indeed a welcome Christmas present."

|

| The only known photo taken of US POWs on Wake Island. Notice the white sun helmets. Nat Archives Photo. |

Three weeks after the fall of Wake,

the POWs awoke to see a large vessel, the

Nita Maru, standing off the

southern shore.

She had arrived to

transport the POWs to camps in China. "About 350 including the key men

were selected and were supposed to stay," wrote Russell.

He became the ranking civilian POW when the

Nita

Maru sailed away.

Another of the

Morrison-Knudsen men, recorded in his diary on 12 January, "All but 360 of

the contractors have been sent to Japan today. [He incorrectly assumed the

destination was Japan.] Also the service men except 21 Marines who are too

badly wounded to go."

"You're already identified as dead and

buried!"

Forty-seven year old Glen Binge was

like many other men on Wake. The

promise of well paying work during a bleak economy lured him far from his

Galesburg, Illinois home. It would be almost four years before

he would see his children again. Binge arrived at Wake on October 27, 1941 on a

nine-month contract. He came ashore

with 175 other men from the USS Curtis (AV-4) a seaplane tender,

which shuttled men and equipment between Honolulu and Wake Atoll.

|

| Pre-War photo of Glen Binge from his local newspaper announcing his capture at Wake Island. |

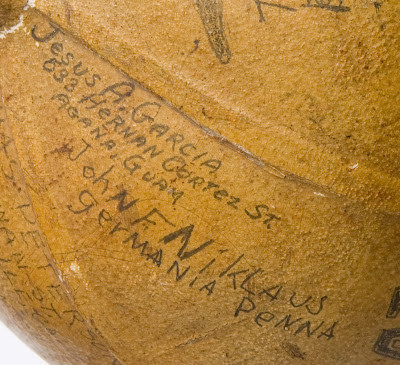

Sometime after January 12th, Binge

began to have men sign his helmet.

Binge's sun helmet was not unusual.

Hundreds of the white sun helmets were issued by the CPNAB to its Wake

Island men.

The Marines issued similar

sun helmets that were tan and bore the Globe & Anchor emblem on the

front.

There is evidence that many men

recorded names of comrades, or had their mates sign their helmets as mementos,

but the Binge helmet is the only one known to have survived.

It has been a family treasure for sixty

years, but its existence has only been brought to light outside of the family

in the past year.

All of the American names inscribed

are from those men who remained on Wake after the departure of the

Nita Maru.

The 360 contractors who remained were chosen

because of their skills in operating heavy equipment.

They would continue the military build-up of Wake Island with the

same supplies and equipment that they had used for the U.S. Navy.

This time, however, the new architects of

the island defenses were the Japanese.

Logan Kay and Fred Stevens remained

hidden in the scrub brush of Wake Island.

They scavenged for food and moved every few days to avoid the

Japanese.

On March 10th, after living

in the bush for seventy-seven days, the fugitives stumbled upon 56 year-old Ted

Hensel of Burbank, Washington.

"You can't be living men.

You're already identified as dead and buried!" Hensel

retorted.

"You two look

terrible.

Better give yourselves

up.

The Japs won't hurt you.

They're treating us fine."

Hensel persuaded the ragged, starving men to

surrender.

|

| Ted Hensel drew a map of Wake Island to go with his sigtature. Courtesy Glen Binge Family. |

"A warning to some who still feel that they have

some rights here."

Leal Russell paints a relatively

optimistic picture of his life as a POW.

His keen eyes recorded the daily coming and going of bombers, fighters,

and ships from Wake as well as the weather and day-to-day activity of the

Japanese garrison.

He seemed to be very

interested in his captors and cultivated cordial relationships with some, even

arranging dental work for one of the Japanese with the U.S. contractor doctor.

Russell surely was aware of the

suffering that was going on around him and indeed that he was probably

experiencing himself.

His tone is up

beat in the diary, however, and he refrains from recording adversity except in

extreme cases.

One such case was the execution

of one of his men who had broken into the Japanese canteen and gotten drunk on

stolen alcohol.

On 8 May, Russell

wrote:

After breakfast I found that they had

arrested Babe Hoffmeister who was out of the compound during the night. Okazaki

told me later he had broken into the canteen. . . I also heard he was drunk. It

is apt to go very hard on Babe as he had been repeatedly warned.

Two days later the Japanese gave Hoffmeister a hasty

trial.

He was found guilty, blindfolded

and marched to his grave.

Logan Kay

recorded:

The Japs made Hoffmeister crouch on

his hands and knees. A Jap officer took

his sword, laid the blade on his neck, brought it back like a golf club and

then down on his neck, severing his head with a single blow.

Of the execution Russell wrote:

"May 10th—Julius 'Babe' Hoffmeister was murdered this morning.

Nearly all foremen and dept. superintendents

were called to witness it.

Possibly it

will serve as a warning to some who still feel that they have some rights

here."

The next morning, with Babe's

murder fresh on their minds, the Japanese evacuated 20 Marines and sailors, who

had been recuperating from wounds, from the atoll.

One of these men was PFC Richard L. Reed of South Whitney, Indiana.

Reed was the only Marine to sign Glen

Binge's helmet.

Reed and the other

recovering GIs sailed away on the

Asama Maru, bound for camps in

China.

Only the civilian contractors

remained to toil for the enemy.

|

| PFC Richard Reed was the only Marine to sign the helmet. Courtesy Glen Binge Family. |

The Japanese did not observe the

Geneva Convention restriction on using POW labor for war-related projects, and

the workers worked at various military projects on all three islands of the

atoll.

Extensive antitank

ditches—protected by slit and communication trenches—were dug on the outer and

inner periphery of all three islands.

Barbed-wire entanglements and land mines provided protection on

potential landing areas.

Inshore from

the narrow beaches, an elaborate system of concrete defenses provided

interlocking fire at almost any point on the atoll.

An estimated 200 concrete and coral pillboxes, bunkers, bomb

proofs, and command posts were constructed with POW labor.

|

| One of the many Japanese defensive structures still extant on Wake Island. Most were made of captured American Portland cement and built with American POW labor. Photo by Author. |

"Rumors fly but even they grow tiresome."

Only the occasional U.S. bombing

raid or Japanese holiday (when no work was performed) punctuated the monotonous

life of the POWs.

Russell wrote:

"Washington's Birthday on Wake Island and still prisoners of the

Japanese.

No change at all. We work, we

eat, we sleep, and then we get up and do it all over again . . . Rumors fly but

even they grow tiresome."

The

rumors of prisoner evacuation became reality on the last day of September

1942.

Two hundred and sixty five

captives, including Glen Binge and twenty-one of his friends who autographed

his helmet, were loaded aboard The

Tachibana Maru and sent to Yokohama,

Japan.

Ninety-eight Americans were

chosen to stay and to continue their work on construction projects.

Most of the men were jubilant that

they were leaving Wake.

They couldn't

know that their lives as POWs on Wake for the previous nine months had been

relatively easy, and that true hell awaited them.