This story is a bit of a departure from my usual

postings. Hart Island is not an

archaeological site and not a tourist destination. (Although it has the

potential to become both someday.) It is

a historic site on many levels, but it is not appreciated or interpreted as

such. I had never heard of Hart Island,

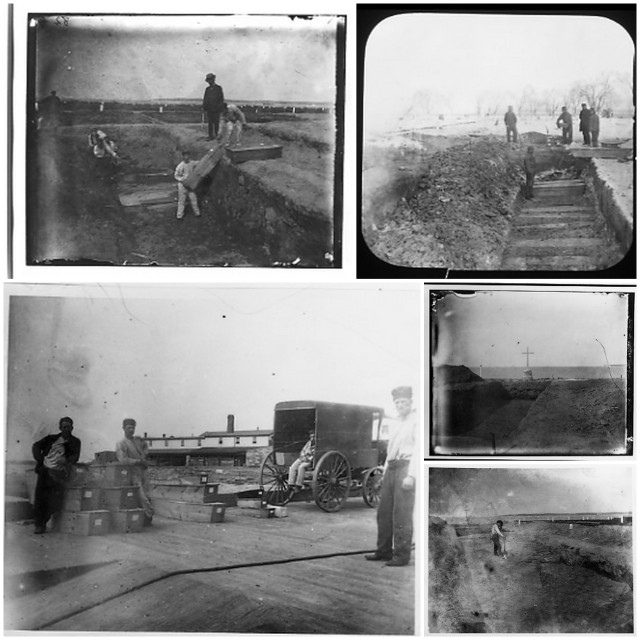

and evidently that is true even for most New Yorkers. "Mass Grave" may be an overstatement as each burial was in individual coffins. However, the graves are dug in "mass" fashion with long trenches to hold hundreds of bodies at a time. I find this story fascinating and re-blog it

in its entirety below.

Re-Blogged from: http://gizmodo.com/what-we-found-at-hart-island-the-largest-mass-grave-in-1460171716

What We Found at Hart Island, The Largest Mass Grave Site in the U.S.

By - Kelsey Campbell-Dollaghan,

It’s a place where few living New Yorkers have ever

set foot, but nearly a million dead ones reside: Hart Island, the United

States’ largest mass grave, which has been closed to the public for 35 years.

It is difficult to visit and off-limits to photographers. But that may be about

to change, as a debate roils over the city’s treatment of the unclaimed dead.

Never heard of Hart? You’re not alone—and that’s part of the problem.

Its most important role has been

to serve as what’s known as a potter’s field, a common gravesite for the city’s

unknown dead. Some 900,000 New Yorkers (or adopted New Yorkers) are buried

here; hauntingly, the majority are interred by prisoners from Riker’s Island

who earn 50 cents an hour digging gravesites and stacking simple wooden boxes

in groups of 150 adults and 1,000 infants. These inmates—most of them very

young, serving out short sentences—are responsible for building the only

memorials on Hart Island: Handmade crosses made of twigs and small offerings of

fruit and candy left behind when a grave is finished.

There are a few ways to end up on Hart Island. One

third of its inhabitants are infants—some parents couldn’t afford a burial,

others didn’t realize what a “city burial” meant when they checked it on the

form. Many of the dead here were homeless, while others were simply unclaimed;

if your body remains at the city morgue for more than two weeks, you, too, will

be sent for burial by a team of prisoners on Hart Island. These practices have

given rise to dozens of cases where parents and families aren’t notified in

time to claim the body of their loved one. It can take months (even years) to

determine whether your missing mom, dad, sibling, or child ended up at Hart.

Even

if you do learn that a friend or loved one is buried at Hart, you won’t be able

to find out exactly where. Though Hart Island is the largest publicly funded

cemetery in the world, it’s been closed to the public since 1976, when the

Department of Corrections took control of the site. Family members can request

a visit on the last Thursday of every month, but they aren’t allowed to visit

specific graves—in fact, there’s no official map (not to mention burial

markers) of the mass graves on Hart. The Hart Island

Project, a nonprofit organization led by an artist named Melinda Hunt, is spearheading the fight to

change that: Hunt has worked for decades to convince the city to transfer

control of the island from the DOC to the Parks Department, making it into a

public cemetery in name, as well as in function. |

| Image copyright Joel Sternfeld and Melinda Hunt. From their 1998 book, Hart Island. |

Part

of her self-assigned job is to liaise with family members searching for

information about their loved ones—like Elaine Joseph, a lifetime New Yorker

and veteran who now serves as Secretary of the Hart Island Project. It’s taken

Joseph more than 30 years to find out that her child was buried on the

island—not an unusual scenario, it turns out, though no less heartbreaking.

It’s women like Joseph, who have come forward to tell their stories, who are

helping Hunt to raise awareness of the gross mishandling of Hart Island.

On

a dreary, lukewarm morning last month, Gizmodo—myself and co-worker Leslie

Horn—along with two other reporters, met Hunt and Joseph in the quaint town of

City Island. They had graciously offered to include us on a tour of the island,

and we were about to become some of the first members of the press to visit

since the 1980s.

|

| Hart Island photographs by Jacob Riis via The Hart Island Project |

35 years ago, Joseph gave birth to a baby girl who needed surgery a few days later. The operation took place at Mount Sinai Hospital during the Great Blizzard of 1978, which shut down the city’s roads and phone lines for days. When a recovering Joseph got through to the hospital, she learned that her baby had died during surgery. Eventually, she was connected with the understaffed city morgue—which informed her that her child had already been buried with other infants. When the death certificate finally arrived, no cemetery was listed.

In city parlance, a blank spot next to the cemetery means one thing: A Hart Island burial. But, in a time before the internet, that fact was lost on anyone without inside knowledge—and Joseph spent the next decade trying to find out where her daughter was buried, visiting the Medical Examiner’s office and digging through the municipal archives. It was as if her child had never been born. “It came to a standstill,” she says, speaking over the phone later. “Over the years, I went on with life.” But every so often, she’d try again—fruitlessly searching the city’s archives for a trace.

|

| Grave of first child to die of AIDS in NYC, with burial documents. Photo by Melinda Hunt via The Hart Island Project |

A few feet away, a small gravestone represents the only sign of a burial memorial. The stone was paid for by the family of the island’s long-time backhoe operator when he passed away. Behind it, a Victorian-era administrative building, likely left over from the island’s one-time psychiatric hospital, lies in ruins. Any real grave markers that remained were removed years ago by the DOC; today, Hart looks like a dreary but nondescript spit of land you might find anywhere else along the mid-Atlantic.

|

| An open burial pit next to the wards in the west of the island. Source: Kingston Lounge |

Hunt

and Joseph pull out a pen-marked map (pieced together by Hunt using satellite imagery)

and try to locate the general direction of where her daughter—along with many

other misplaced infants from the same year—might lie. It’s woefully inadequate,

not to mention unnecessary given the advent of GPS. Even if the DOC doesn’t

create markers for each gravesite, they could certainly make the information

available online. But Hart—right down to its decaying Victorian buildings—is

stuck in the past. As Hunt explains, much of the way Hart operates dates from

the Civil War. “This is a very 19th century kind of place,” she adds.

But it doesn’t have to be. Hunt,

who qualifies as nothing short of a hero, is working to extract answers to

painful questions—not only at the personal level, but at a legal one. Do loved

ones have a legal right to visit a family gravesite? In some states—mostly in

the South, where Civil War graves often lie on private land—yes. But, in New

York, things are more ambiguous: State public health laws codify the common law

right to a decent burial, but it is unclear whether that includes the right to

visitation. In 2012, a New York Ob/Gyn named Dr. Laurie Grant, whose stillborn

daughter was buried on Hart Island without her consent in 1993, brought a lawsuit

in New York State Court seeking an injunction against the DOC that would allow

her to visit the gravesite. |

| One of the mass graves that fit up to 150 adult coffins. Source: Kingston Lounge |

Such a sad story Mark. It sounds very much like the Crete story called "The Island " which was once a leper colony.

ReplyDeleteWow. Shocking in these days and times.

ReplyDelete