"I ate anything to stay alive"

Fukuoka No 18-B became the new home for the remaining 260. This camp, near Sasebo Japan, was established to provide slave labor for the construction of Soto Dam. The work was backbreaking and the rations slim. Three small bowls of soupy rice per day was the standard fare. One inmate confessed, "I ate garbage while at Camp 18. A man will do anything for food if he is really hungry."

The meager diet was enforced even if additional rations were available. The Japanese pilfered or withheld Red Cross packages and punished men for "garbaging," trying to steal offal and vegetable peelings from Korean laborers. One inmate who was six feet four inches tall was reduced to 110 pounds. "I ate anything to stay alive. . . I ate toads, roots, grasshoppers - you string 'em on a wire and throw them in a fire, then eat 'em like peanuts."

|

| US Sailors visit the Soto Dam in Japan during a ceremony to honor the 53 American POWs who died during its construction. |

A series of heartless commanders and senseless beatings by brutal guards exacted a horrible toll on the Wake Island men. The slightest infraction of the rules brought extended beatings with clubs and baseball bats. One survivor was hit repeatedly on the forehead with a rock by a Japanese guard. "I thought my brains were going to explode," he remembered.

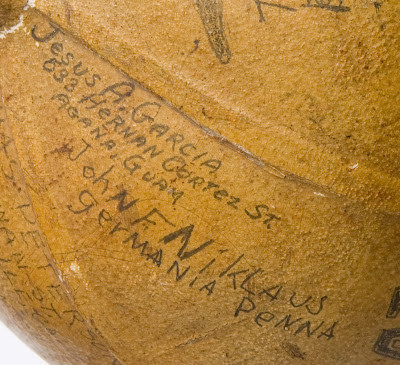

Jesus Garcia, the Guamanian who had worked at the Pan American Hotel, barley escaped with his life. He was pushed from a guard tower, and then beaten on the head with bamboo club for an hour.

|

| Jesus Garcia signed just above John Niklaus. Niklaus was the first of the Helmet signers to die. Courtesy Glen Binge Family |

The first of the helmet signers to

die was John F. Niklaus of Germania, Pennsylvania on January 26, 1943. Japanese records claim he died of

"acute pneumonia." Julius

Larson of Healy, Idaho, was next on February 18th. James H. O'Neal of Worland, Wyoming followed on February

27th. The Japanese listed the cause of

death for O'neal as "cardiac beri beri." Acute pneumonia also claimed Andrew Nygard of Long Island, New

York on March 13th.

|

| Dick Myers was beaten to death on April 29, 1943. Courtesy Glen Binge Family |

The next to die was Ted Hensel on May 5, 1943. Hensel was the man who convinced Logan Kay and Fred Stevens to surrender back on Wake Island. Norman Hill of Clarkston, Oregon succumbed to "malnutrition" on June 4, 1943. The last of the helmet signers to die at Fukuoka No 18-B was Lloyd Kent of Burbank, California who passed away on March 3, 1944.

Thirty-seven year old Oreal Johnson of Boise, Idaho served as the chaplain and lay preacher for the Wake Island men. He provided a short service for each funeral and sang I Need Thee Every Hour. Johnson and other men of the burial details were rewarded for their loathsome duties with extra food. The guards enjoyed tossing the rice balls among the starving men to see the melee that would ensure. By April 17, 1944 when the Wake Island men were moved to Fukuoka No 1, Fifty-three of the original 260 were dead.

|

| Rodney Kephart and Oreal Johnson survived Fukuoka #18. Johnson served as Chaplain during funerals of fellow POWs. Courtesy Glen Binge Family |

Fukouka No. 1 was a large camp that housed American, Australian, British and Dutch POWs. Conditions improved to some degree at No. 1. The rations were still sparse, but some Red Cross packages did get through. The Japanese guards more often slapped their charges around instead of beating them with clubs. The biggest difference was the nature of the work. They built a new airfield at No. 1 and avoided the backbreaking labor that had killed so many men at the Soto Dam.

The death rate plummeted and no more signers of Glen Binge's helmet met their end after leaving Fukouka N.18-B. Binge also began to make friends outside his Wake Island family at No. 1. Gunner William Davis, and Sgt Benjamin Regan, both from London and veterans of the Royal Artillery, added their names to the helmet. The outside was covered with autographs, so they scrawled their names on the inside of the crown next to where Glen had placed his own mark so many months before. Dutch soldiers, H. Buys, W.F. Zonneaberg and P. Van Veen signed near their British allies. By enlarging his network of friends outside of his immediate circle, Binge also broadened his potential access to resources. This may have contributed to his survival.

|

| William Davis of London England was one of five allied soldiers who signed Binges Helmet. Courtesy Glen Binge Family |

"Can you make us an American Flag?"

During the last year of the war the

surviving men who were evacuated from Wake in September 1942 began to be

separated. Labor details were

dispatched away from Fukouda No. 1 without regard to the men's original

organizations.

In late August 1945 red, white and blue parachutes began floating to earth above food cartons at Fukouda No.6 near Orio, Japan. Japan surrendered and hostilities ceased on August 15th. American bombers began parachuting food and clothing to the starving allied POWs at camps all across Japan. On the morning of September 1, 1945 several of the officer POWs approached Rodney Kephart with an armload of silk canopies.

"Can you make us an American flag so we can have a official raising of the colors at the same time the Japanese sign the surrender tomorrow morning?" they asked. The POWs had learned that the official surrender ceremony was to take place the following day. Kephart was the only man who knew how to operate a temperamental Japanese sewing machine at the camp. Kephart and another POW, worked sixteen hours straight to have the flag ready in time. He was too exhausted and overcome with emotion to attend the ceremony. He lay in his bunk sobbing as his flag was raised over the camp.

|

| Rodney Kephart's flag made from parachutes. From: ttp://home.comcast.net/~winjerd/Kephart.htm |

Logan Kay and Fred Stevens, the men who hid out for so long on Wake, somehow managed to remain together. They were liberated on September 19, 1945 at Camp No. 23 at Izuka, Japan. George Weller, a war correspondent for the Chicago Daily News accompanied the liberation teams and met Kay at Camp No. 23. Weller recorded Kay's remarkable story and transcribed the diary he kept while on Wake. Weller and Kay were photographed with a white sun helmet that bore the names of Wake Island dead. Much like Glen Binge, Kay had saved his own souvenir helmet that bore the names of scores of Wake Island men. That photograph was published in the Chicago Daily News with the caption "Memento of Terror." It is not known if Scotty Kay's sun helmet has survived.

|

| From: http://www.historylecture.org/wakeisland.html |

As the survivors of the hell camp at Fukouka N.18-B began their long journeys home to the United States, they did not know that all ninety-eight of their comrades left on lonely Wake Atoll had been dead for almost two years.

Next Time - Part Four - http://erasgone.blogspot.com/2012/09/a-wake-island-helmet-part-four.html

Thanks for the great story about these forgotten heros.

ReplyDeleteMark Lewis

Mark, I'm glad you are enjoying the series. Come back often. Please consider signing up for email notifications if you cannot "follow" the blog as a blogger.com member. Thanks again!

DeleteThank you for the photo of my father's name - O.J.Johnson. I would know his writing anywhere.

ReplyDeleteWe have been searching for information about my grandfather for many years. Archie H. Pratt was one of the civilians on Wake. Scoured your story looking for any mention of him. We'll never stop searching.

ReplyDeleteMy grandfather Norman Lester Hill lived in Clarkston, Washington.

ReplyDeleteMy grandfather was Leal Henderson Russell. I appreciate having found this blog - thank you. Stephanie Russell Persson

ReplyDelete